Progress Highlighted as Fifth Person Cured of HIV

Researchers in Germany announced a fifth person has been cured of HIV.

In a study published in Nature Medicine, researchers from University Hospital Düsseldorf detailed the treatment of the 53-year-old patient, known as “the Düsseldorf patient” to protect his privacy, who was diagnosed with HIV in 2008 and acute myeloid leukemia three years later. He received a stem cell transplant in 2013 as part of his treatment for the cancer – which also cured him of HIV.

Despite the development, a widespread cure for the virus, which attacks the body’s immune system, may still be a long way out.

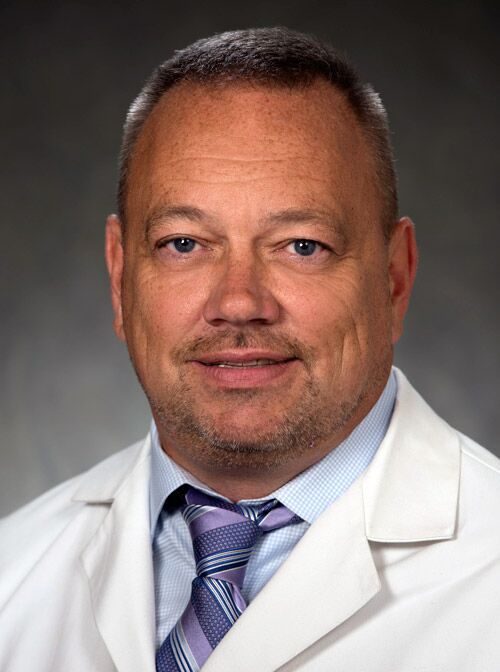

“It’s definitely promising, however, it’s unlikely that stem cell transplants would be performed for people living with HIV who do not have leukemia,” said Dr. William R. Short, the chair of the Board of Directors for the American Academy of HIV Medicine.

Stem cell transplants are most often used to treat people with leukemia and lymphoma by replacing damaged or destroyed blood cells with donor blood cells. The procedure is considered risky as it has high morbidity and mortality rates.

The case was rare because the female donor had a mutation called CCR5Δ32 that is believed to confer resistance to the HIV infection, said Short, who is the associate director of the AIDS Clinical Trial Unit research site at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. Because the mutation has a frequency of about 10% in populations of European descent it is difficult to find potential donors who both carry the mutation and are a match for the patient.

The research does, however, show that HIV treatment and therapies have radically changed in the last thirty years.

“There was a time in this world where if you were diagnosed with HIV, you didn’t really have long to live,” said Bishar Jenkins Jr., the policy director for AIDS United. “And it’s stunning, the progress that we’ve made over the past decades.”

When someone is diagnosed with HIV today treatment is started right away, sometimes as soon as the day of diagnosis.

Doctors prescribe patients with what is known as combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), which uses a minimum of two drugs, usually three, from different drug classes that target two separate aspects of the virus’s lifecycle. The therapy paralyzes the virus and prevents it from infecting other cells.

“There was a time in this world where if you were diagnosed with HIV, you didn’t really have long to live,”

said Bishar Jenkins, the policy director for AIDS United.

The use of cART has been a game changer for people living with HIV.

“Antiretroviral therapy has basically transformed HIV from a once terminal illness, and unfortunately in my lifetime I got to see that, you know, when I was in my twenties and in college, I got to see people who were diagnosed and dead within a couple of months,” Short said, “and now it’s a manageable chronic illness.”

Patients currently take a once daily pill or, as recently as January 2021, twice monthly or every other month injections. Because a reservoir of the virus persists in the immune system, blocked by the therapy from spreading but not eliminated from the body either, cART is a lifelong treatment.

“We are not shy of work here,”

said Dr. William R. Short, the associate director of the AIDS Clinical Trial Unit research site at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine.

The reservoir remains a challenge for doctors and while cART is not a cure, patients are able to reduce their viral load to the point it is undetectable. If their viral load is less than 200 copies per mL for more than six months, they cannot transmit the virus to anybody. This concept is known as undetectable equals untransmittable, or U=U, and has radically changed the lives of people living with HIV.

“People are able to live long, healthy lives with HIV if they have access to care,” Jenkins said.

Short said the goal is to expand the therapy into once-a-week pills and, ultimately, treatment once every six months. All of these could provide a roadmap to getting around the barrier of treating HIV.

“There’s still ongoing treatment trials,” he said. “We are not shy of work here.”

“The progress that’s been made is really progress made because we’ve had people that literally fought until they died,”

said Bishar Jenkins, the policy director for AIDS United

Access to this care, Jenkins and Short said, remains a priority in ending the HIV epidemic.

“We really have to remove those barriers that exist just to get people into care, and stay in care,” Jenkins said. “And then once people are in care, there are other institutional barriers that exist particularly for people of color, and for people that are marginalized LGBTQ folks as well, within healthcare settings because we know the way in which communities of color and LGBTQ folks tend to be viewed from certain people in society.”

Believing that only certain people can get HIV; making moral judgments about people who take steps to prevent HIV transmission such as taking PrEP, a medication taken to prevent getting HIV; medical professionals refusing to provide care to a person with HIV and social isolation can all cause people to avoid or be denied treatment for the virus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Stigma, stigma, stigma is the main thing,” Short said. “The perception of people with HIV is changing within the healthcare system. It’s changing.”

In the early decades of the epidemic the discrimination of those with HIV often prevented lawmakers from allocating money to research, care and prevention of the virus. In the 80s, affected individuals formed advocacy groups, such as ACT UP, to directly target this void.

“The progress that’s been made is really progress made because we’ve had people that literally fought until they died,” Jenkins said. “And then we have also benefited from activists that have survived, that are long term survivors that have been doing this work for 40 years now, since the beginning of the epidemic.”

The organization Jenkins works for, AIDS United, provides grants to groups that are directly involved in community organizing. These groups may provide care for people living with HIV, financial support as they seek treatment or resources for prevention.

“It’s really important because community-based organizations are connected to the people that are most impacted by HIV,” he said. “Oftentimes, those people have connections and buy in with the community in ways that larger institutions and health centers, for example, don’t have.”

Jenkins said he hopes access to HIV therapies progress along with the science.

“We know that the people that are most vulnerable to HIV don’t have access to that medication, or don’t take that medication for a number of reasons,” he said. “And my sincere hope is that everyone that is vulnerable to HIV has access to that medication.”