HOW TO MAKE IT TO COLLEGE BALL: THE NUMBERS AND STEPS TO FOLLOW

Think you could have made it into college sports?

Maybe you should look at the numbers.

Many people dream of making it to the next level of their sport. Representing a college is something that only the elite of the elite get to experience.

GMTM reports that roughly only 2% of high school athletes go on to play their sport at the division one level.

It varies greatly by sport. For example, in men’s ice hockey, 4.8% of high school athletes make it to the division one level, and in women’s ice hockey, 8.9% make it to division one, according to the NCAA .

The lowest for men’s and women’s sports is .7% in men’s volleyball, which could be because there aren’t as many high school players and for women it is basketball at 1.3% which could be because the NCAA isn’t equal on their treatment of women’s sports in comparison to men’s USA Today tells.

The recruitment process can be a very exciting, yet frightening moment for everyone, especially when coaches start talking.

It starts with colleges gathering information and statistics on players. Following that are letters of recruitment and camp invites, perform good enough at the camps and then the athlete might just be lucky enough to earn an offer next and if they decide that school is their home, they sign.

Next, the coaches decide if they should give the player a scholarship or not.

A big reason why the turnover rate between high school to collegiate athletics is due to the amount of scholarship each sport receives.

Ed Egan is a former high school coach and currently an athletic recruiter. “Depending on the level that you choose to go, that will decide if you are able to get the offer that you have been looking for, ” he said.

“NAIA (National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics) can have up to that many players (85) splitting it only 24 ways and division three can’t even offer athletic scholarships, only academics,” Egan said.

At the high school level, it is more common to see everyone at roughly the same size and strength.

At the division one level, the ones who make it are going to be the ones who have big size and strength along with the skill.

“There has to be luck involved and size, that’s just the facts of the recruitment process,” Egan said.

“Yeah, I think that I could have played college ball if I was two or three inches tall and maybe 50 to 100 pounds heavier.”

Ryan MollohaN, FORMER FOOTBALL PLAYER

Former football player and current University of Akron student Ryan Mollohan played on the offensive line at Coventry High school.

“Yeah, I think that I could have played college ball if I was two or three inches taller and maybe 50 to 100 pounds heavier, ” Mollohan said.

This is true in women’s athletics as well. .

Overall, the average height of a division one volleyball player is around 5 ’10” and 5’6” for basketball according to NCSA reports.

There are roughly 2.4 million women athletes playing sports in high school. Of those, only about 7% go on to play college sports at any level.

For men there are about 4.2 million athletes in high school with only 6% making it to the next level.

“I got recruited pretty heavily, not by any big teams but a lot of division three schools,” Mollohan said. “Mainly schools like Mount Union or John Carroll or small schools in the country of Pennsylvania.”

“I just want what’s best for my kids.”

Jimmy Mashburn, Stow Football Coach

Jimmy Mashburn

Having a good coach makes it a little easier to get to the next level.

“I just want the best for my kids,” Stow football coach Jimmy Mashburn says. “Winning is the number one goal for me, but after that it’s trying to grow my athletes into being ready for the next step.”

Mashburn was also recruited out of high school.

“I went and played a season of football at Muskingum University, then I just didn’t like it. I felt like my heart wasn’t in it,” Mashburn said.

For some, a turn off from division three, JUCO and NAIA is that you may not get a scholarship at all.

“It would’ve been hard,” Mollohan said. “Most of those small division three schools are private and triple if not more the price of public schools.”

College sports scholarships reports that the average cost of tuition for a year at a division three college is around 27,000 dollars in the northeast region .

This doesn’t mean that division three colleges aren’t good for athletics though.

Mount Union has 13 national championship winning football teams. That’s more than Ohio State, Michigan, Georgia and LSU have, and is tied with Alabama.

Getting a college coach’s attention for any sport can be next to impossible, so what should you do?

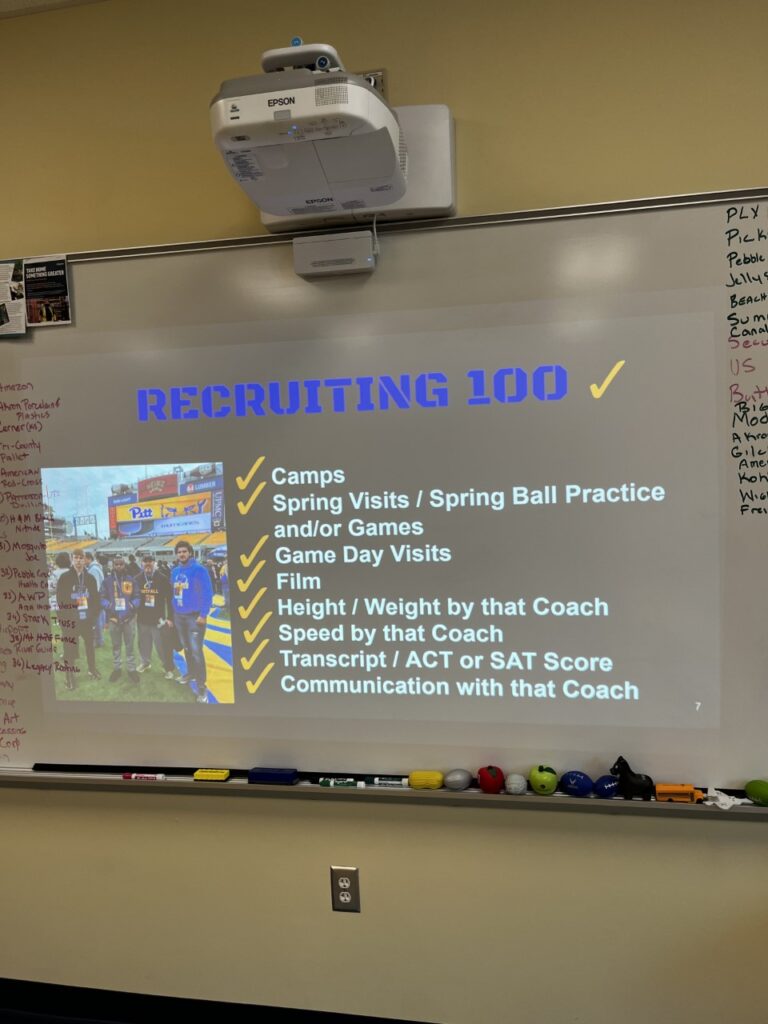

Egan breaks down the steps that an athlete should follow in order to get on the radar.

“Twitter is a necessity,” Egan said. ”That platform has become sort of like a resume for athletes. It can tell me everything I need to know about the person in just a few clicks.”

Former football player and current Akron police officer in training, Brandon Kreiner agrees, “I didn’t even have a Twitter before high school. My coach made me get one because he was so heavily involved with social media and liked how it allowed coaches to be able to find you easier.”

There are also great platforms that you can use to make highlight tapes for any sports called HUDL.

Egan says that he would make all of his former players send him the plays they liked best and he would make a reel for them for their Twitter.

“It was nice getting to meet new coaches and getting my name out there.”

Brandon Kreiner, Former football player

“Going to camps is also a huge part of recruitment. If you don’t put yourself out there, they will never find you,” Egan said.

If the athlete sends in their film or doesn’t sit in the background at camps, they have more of a chance of getting that offer.

“Camps are where the best competition is,” Mollohan said.

The athletes that go to the camps are the ones that are serious about their sport and are doing whatever it takes to make it to the next level.

“It was nice getting to meet new coaches and getting my name out there,” Kreiner said.

Coaches won’t know the athlete until they have a direct interaction with them, this can be what sets athletes apart.

“Taking my players to camps and seeing them perform against the best of the best makes me feel like all that hard work is finally having something to show for,” Mashburn said.

Many high school coaches train their athletes for these camps so they can be prepared properly.

“If you don’t talk to them, they are going to move onto the next athlete waiting in line without thinking twice.”

Ed Egan, Recruiter

“Next, I would go on a visit,” Egan said. “Whether that be to spring games, practices, games or whatever else it may be it is very important to go on those visits and have a conversation with the coaches. If you don’t talk to them they’re going to move onto the next athlete waiting in line without thinking twice.”

These visits don’t get handed out to just anyone Egan says.

A helpful resource that an athlete can use is a checklist of events or duties they must accomplish to get their name out.

“If you get an invite to let’s say a game, then they want you and are heavily considering offering you a spot on their roster,” Egan said.

Whether you’re a woman or man, football player or water polo player, the odds of making college athletics are slim.

This doesn’t mean that it won’t happen, but it does mean that you have to go out of your way to make it happen.

“Unless you’re the very best of the best, you’re going to have to sacrifice something,” Mashburn said.

It comes down to school work, too.

For division one hopefuls, they have to maintain at least a 2.3 GPA in high school or else they can’t be offered a scholarship.

A scholarship also could be offered but if by the time the athlete graduates and their grades are below the needed GPA then that school could also revoke the offer entirely.

“That’s always the worst,” Egan said. “When you see a kid with all the talent in the world but they just can’t keep their GPA up enough and they almost waste their potential.”

Teams in college also have their own GPA that student-athletes must fulfill in order to play.

“If you can keep your head down, and get through all of the tough stuff,” Egan said. “Eventually you might see yourself on a college roster.”